Scarpa and the art of Mineral Ascent

By Pierre Bidaud

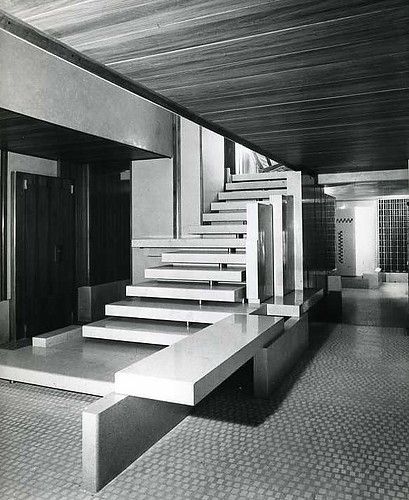

It was through a dirty window that I was first acquainted with the Olivetti showroom’s stone staircase in Venezia. This first glimpse was going to stay with me for a very long time. Of all the staircases I have seen and used I found this to be the most intriguing, and my personal favourite.

I was introduced to the great architect Carlos Scarpa (1906-1978) by an Italian ex-girlfriend and it was a revelation (both my girlfriend and Scarpa were revelations, however one was going to stay with me a lot longer than the other, and yes, it was Scarpa).

Picture 1

Our first visit to Veneto and Venice was to be a discovery of some of Scarpa’s key works. I was mesmerised by the deconstruction of space at the Querini Stampalia, the natural light from corner windows bathing the cast of Canova’s goddess at the Possagno Museum and the orderly concretion of metal in the connections of the cabinet supports at the Correr museum

In 1957 Olivetti typewriters were at the top of their game, and to promote their incredible new machines they needed an architect that was of the time, bold and innovative. The resulting Olivetti showroom with its rich use of natural material including stone, tiles and wood, as well as exquisite iron and brass work, showcased not only Olivetti’s products but also the impeccable local craftsmanship, showing to the world, from its wealthiest art city, that Italy was still relevant. The firm wanted to show that it was redefining post war Italy, so much so that in the same year Olivetti commissioned Sottsass to design their latest range of typewriters.

Picture 2

It was the Olivetti shop in Piazza di San Marco that blew me away. For a stonemason like myself the side elevation of the shop itself was a quartet of texture mixed in a disorderly fashion, with finely carved “Olivetti” lettering projecting from the raw material, this elevation alone could have its own blog article! The use of so many finishes and the elegantly detailed connections between them, unnecessary interfaces that make complete sense, with the shop window itself opening up to the most incredible cascade of stone steps.

At the time of my visit the Olivetti store had not been restored, and I had to squash my face against the dirty glass to get a better idea of what lay beyond, the single flight stone staircase, leading from the ground floor to first floor can be seen from the shop window, when looked at from the side the Aurisina Marble steps have a sort of awkward balancing act, a thin tread at the front with a heavy counterweight at the back. It seemed that Scarpa had created a traditional stone staircase but decided to compress the structure and then unfolded it (See Picture 3) It reminded me of the Maegth museum staircase near Nice by Josep Lluís Sert (See Picture 4). This organization, with steps clamped to one other would be developed and improved upon in Scarpa’s later works (See Picture 5).

Picture 3 (Pictures 4 and 5 Below)

The steps at the Olivetti shop however are installed on rough rectangular concrete slabs laid on their side, horizontally fitted, and staggered with Scarpa’s trademark recess. At the time I could only see the side, but I could see that the staircase had a sort of plinth for a curtail step, like some long steps with a curb, placed head to toe, like a mineral pontoon, hovering above the mosaic of dirty glazed tiles. That plinth serves as a reminder that you are in Venice and that the San Marco piazza is often submerged.

I had to wait for 3 years to be able to visit the restored shop and enjoy it from all of the other vantage points. This staircase is so ground breaking in so many ways. As you access it from the front all of the steps seem to hover, as you go up the hard limestone steps are slightly staggered and 2 of the risers, numbers 2 and 6, are extended so they can become plinths upon which the typewriters or calculators can be showcased. The 6th steps is so extended that it looks almost like the chariot of a typewriter pushed to its maximum. Looking at this step profile more closely you can see that the steps edges are slightly rounded with a very shallow curve (See picture 6), and squashed between the overhanging steps you can also see the round, solid bronze, spigots, counteracting the unbalanced structure.

Picture 6

There is no balustrade and the staircase suddenly gets squashed between the 2 supporting walls of the 1st floor, the right hand side of the staircase is flanked by some tall, staggered, rectangular slabs, again forming a horizontal staircase, a kind of separation between the 2 rooms.

All of these crafted elements are textured to reinforce their purposes, the bush hammering of the concrete supporting wall, polished and round edged steps, detailed and less sharp vertical slabs as well as crisp bronze spigots create a logically articulate staircase. Between each stone the joints are left open, a tight gap, as thin as one would draw with a pencil, reinforces the impression of disconnection,

This whole lateral movement of the steps as you go down makes you feel like you are going down a cliff-top stone path leading to the beach, the, now clean, glazed tiles gleaming like the quiet Adriatic Sea.

While writing this piece, looking at old pictures, it strikes me that the staircase could be a simple tectonic sculpture all on its own. The different planes (vertical and horizontal) cutting into each other, the staggering of the slabs, off setting in increments, the strange balancing act of the steps, it really looks like a sort of cubist reinterpretation of a cliff, an escarpment- which in Italian translates to Scarpa.

While Carlo Scarpa was working in 1978, producing some key works, including the famous Castle Vecchio refurbishment and private cemetery, it was painful to learn that he died of a fall on a staircase. For spectators and users of Scarpa’s staircases however the biggest risk is being blinded by his genius, love of craftsmanship and dedication to originality.